Posts filed under ‘Medusa’

Rhodian Medusa II

In the last blog I presented the ideograms, abstract small images that the artist used in a symbolic way to enhance the figure and show that she meant it to represent the great goddess, lady of life in death. I also discussed the belt, the one object that I know that has a link to contemporary literature, in this case Homer.

The Head

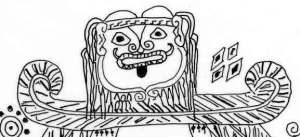

The outline of the cheeks and chin look like a Bronze Age necklace open at the back and with two spirals as a clasp. The ears are large double spirals and placed near the hair-line. The hair is designed as very elongated triangles and continues round the head to the clasp that constitutes the chin. It makes the head look like a mask placed on top of the wings on the shoulders and the impression is strengthened by the hair, well combed and parted in the middle that is visible above the hair-band. This band is also decorated with a pattern inherited from the Bronze Age: running zetas.

The eyes are shaped like rhombs similar to the rhombs placed in a cross-like position to the left and right of the figure.

Two spirals at the end of a triangle make the nose and the mouth is oblong with rounded corners. The teeth are placed on the lips. Two small tusks are placed like two opposing crescents above the mouth with the tongue hanging from the lower lip.

This is not a primitive portrait, but a highly symbolic image (I use symbol/symbolic in the Jungian way: the best possible image of an abstract concept that is too large to be expressed in any other way but through analogues taken from our physical world).

To my knowledge, this is the earliest mask of the Lady Medusa and it seems probable that it has in some way served as a prototype. It is not the first image after the one found in Thebes, Boeotia, There exists another image in between. It comes from the sanctuary of Eleusis not far from Athens and shows Sthenno and Euryale leaving the head-less Medusa. They are not centaurs, neither do they carry masks. Marija Gimbutas thinks that they are bees, but they do look more like the bronze cauldrons in fashion at the time of the painting.

To my knowledge, this is the earliest mask of the Lady Medusa and it seems probable that it has in some way served as a prototype. It is not the first image after the one found in Thebes, Boeotia, There exists another image in between. It comes from the sanctuary of Eleusis not far from Athens and shows Sthenno and Euryale leaving the head-less Medusa. They are not centaurs, neither do they carry masks. Marija Gimbutas thinks that they are bees, but they do look more like the bronze cauldrons in fashion at the time of the painting.

(I do agree: I would be terrified meeting a centaur or one of my pots transformed into the head of a non-human woman.)

The prominence of the spirals on the face and along the rim certainly was not lost on the ancient onlookers. The spiral is a road that leads in to the center and then out again. on this plate once placed in a tomb it leads the deceased person to the center that is death and from there back to the entrance/exit that is life .

In some way the spirals continue to belong to the Lady Medusa even much later as this image shows that was painted 150 years later.

In some way the spirals continue to belong to the Lady Medusa even much later as this image shows that was painted 150 years later.

The Eyes

Now we turn to the Lady’s eyes that according to the myth and tradition kill everybody she looks at.

We know that the Greeks believed in the evil eye and used amulets against it. Of course, we don’t believe in it. It is, however, interesting that in Star Wars the Emperor, George Lukas’ personification of evil, is an old man with red rimmed eyes. In the Iliad, the poet only mentions the Gorgon’s eyes once (8:349) when he describes Hector, the Trojan hero, whose eyes blaze like those of Medusa and the god of battle, Ares, “killer of men.” However, we must not forget that Hector is a favorite of Homer, who describes him in a different and more positive way than any of the Greek warriors. His eyes blaze like those of the Immortals – like Athena’s when she makes her champion Achilles recognize her: “It is terrifying to see the light of your eyes.” (1:200)

Until modern science proved the contrary, people imagined that the eyes sent out beams of light thus both showing individual feelings and capturing the world. We still say that eyes shoot a look of anger, which is implied in Matt.6,22: “The eye is the lamp of the body.” During the Neolithic period all over the world, the most common way of representing eyes on female figures is the pictogram of the vulva.

One of the analogies is probably that as the child is born into the world through the vulva, so the goddess creates life through sending out the light from her eyes into the world. When the positive symbol was forgotten, Medusa’s killing eyes took its place.

The Tusks

Hebraism, Christianity, and Islam have transformed the pig that over the whole earth has lent its tusks to important deities, into such a dirty animal that it is difficult to understand how it once has been a suitable image of the goddess. However, this is not true in other cultures. In his autobiography the present Dalai Lama tells the legend about the goddess Vajravahari, “Adamantine Sow.” She manifests herself as a woman with the head of a wild sow. In the eighteenth century some Mongolian warriors entered by force into the Samding monastery where they found the monks in the assembly hall and a big wild pig sitting on the throne of the abbess. They fled.

Several seals with images of wild pigs were found in Minoan tombs. Pottery pigs are common in tombs in Greece, South Italy and Etruria, and in Chinese tombs from the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE). In Rome the sacrifice at the death of a family member consisted of a pig, as even now in New Guinea. In classical Greece sows were sacrificed to Demeter, Athena and Hera; wild pigs to Artemis. During the Thesmophoria piglets – pigs-to-be – were given to the not-yet-fertile Earth.

Several seals with images of wild pigs were found in Minoan tombs. Pottery pigs are common in tombs in Greece, South Italy and Etruria, and in Chinese tombs from the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE). In Rome the sacrifice at the death of a family member consisted of a pig, as even now in New Guinea. In classical Greece sows were sacrificed to Demeter, Athena and Hera; wild pigs to Artemis. During the Thesmophoria piglets – pigs-to-be – were given to the not-yet-fertile Earth.

We define ourselves in the world not only by integrating ourselves in it, but also by opposing ourselves to it.

I like how Stanley Walens (Encyclopedia of Religions, vol. 1, 1987) expresses it:

[Animals] represent the antinomies of living, the existence of the sacred in the profane, the wild in the civilized . . . They enable us to create analogies. At their most simplistic, such analogies might state that animals are to humans as humans are to gods.

The wild pig is stronger and faster than a human being; its beauty is different from ours and it is as far from us as we are from the divine persons. The wild pig is dangerous and, when necessary, ready to kill. However, because its tusks are shaped as the moon’s crescents, it reminds us of the fact that the moon is born again and gives birth again after three black nights.

According to Robert Graves, the Orphics called the full moon “Gorgon’s head.” The name of Medusa’s human son is Chrysaor, “Sword of gold.” He is the golden sickle, that is, the new moon – and the dying moon that kills. All the indications point towards the Lady Medusa being a symbol of the moon.

The Moon

Living as we do with electric lamps lightening the nights, we forget the importance of the moon. In southern latitudes and in places without electricity its impact is enormous. I remember my first excavation on the island of Chios where we had no electricity. On nights of the full moon we all remained seated far into the night, hypnotized by the moon. We did not talk, we just sat staring into its face.

Alexander Marshack has shown that calculations of the moon’s growing and waning phases exist in the Upper Paleolithic Period. The old age of these observations may be why the moon is so ambiguous: it is feminine and masculine, it gives birth and it impregnates women. It is forever present and forever changing.

Although the moon in many places is regarded as male, it is feminine in the Mediterranean area. The new moon is born; in the second quarter it grows, and when it is full it represents a circle: the symbol of unity and fullness. Then it declines, grows old, and dies. For three nights the black moon is dead, then it is born again month after month after month.

In analogy to the moon the lunar Goddess gives birth, sustains, and kills. Sri Ramakrishna, the great Indian saint, has given us an example of this. He saw in a vision Kālī, the Great Mother, (who is a Moon Goddess) as a young woman coming up from the river Ganges. The woman gave birth to a child and laid it to her breast. She then killed the child, grew old and returned to the river. As Kālī, Athena and Artemis are lunar goddesses of birth and death and so, I think, is Medusa.

In analogy to the moon the lunar Goddess gives birth, sustains, and kills. Sri Ramakrishna, the great Indian saint, has given us an example of this. He saw in a vision Kālī, the Great Mother, (who is a Moon Goddess) as a young woman coming up from the river Ganges. The woman gave birth to a child and laid it to her breast. She then killed the child, grew old and returned to the river. As Kālī, Athena and Artemis are lunar goddesses of birth and death and so, I think, is Medusa.

******

Illustrations:

The Great Goddess from Rhodos. Inside of a plate from a tomb in Kamiros, Rhodos, now in the British Museum Acc. 60.4-4-2. After Hirmer 561.0248 , Photo Archive, Getty Library, Malibu. Drawing K.B.The head of Sthenno or Euryale. Detail of amphora from Eleusis, ca. 670 BC. After E.G. Mylonas, O protoattikos amphoreus tes Eleusinos. 1957. Drawing K.B.

Head of the Gorgo. Centerpiece of Athena’s shield on a Red-Figured amphora by the Berlin Painter. 490-470 BC. Antikenmuseum Basel. Drawing K.B.

Wooden mask of Rangda, Bali. Private collection. Photo K.B.

The Goddess Kali, 1940s Poster art. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/kali

The Rhodian Medusa I

Around 690 BC a potter-artist from the island of Tenos delivers a big vase to somebody important in Thebes, Boeotia (the region north of Athens). On the neck the image shows how the young Perseus killes the Potnia Gorgo Medusa, the Lady, Mistress of the Horse. For the next three hundred years, the image of the killed Medusa will be the preferred one in the patriarchal Athenian society.

One or two generations later, another potter makes a plate on the island of Rhodos that is going to influence a larger part of the Greek society: those living in the cities on the Peloponnese, Crete, the west coast of Asia Minor (present Turkey) and the south coast of Italy. Here the Lady appears wearing a mask and with the attributes that belong to the goddess who reigns over life and death.

Rhodos is a big island in the south-east corner of the Greek archipelagos. According to the ancient tradition the Greek population there was very ancient. We don’t know if they spoke the Doric dialect fom the beginning or if these Greeks immigrated later. In any case there are no signs of a war-like invasion.

People speaking the Doric dialect thought and acted differently than the Athenians did especially in the case of the female population. While the Athenians were fiercly patriarchal in the Doric-speaking cities women and men had equal rights.

During the seventh and sixth centuries these cities had a flourishing cultural life that was barely beginning in the small and rural Athens.

The island of Rhodos had three important cities: Rhodos, Kamiros and Lindos. The goddess Lindia was the principal divinity. Later the inhabitants began calling her Athena, but only in the second part of the fourth century, under pressure from Athens, did they allow Zeus to sit beside her in her most important temples.

***

The plate on which the image of Medusa is painted is dated between 650-630 BC.

The plate on which the image of Medusa is painted is dated between 650-630 BC.

It comes from a tomb in Kamiros that was excavated in 1860 or 1863-64 by August Salzmann and Alfred Biliotti who sold it to the British Museum.

Medusa walks. She has one waterbird at each leg, but she is not holding them; her hands are held wide open in front of their heads. She dresses in a skirt that is open in front and shows one of her very muscular legs. The dress is held together by a broad belt.

The Lady is too big to fit into the circle mady by the plate: her feet pierce it. In later images she crouches; there is absolutely not enough space for her in the human realm. (Picasso, too uses this device when he draws goddesses seated in far too small rooms.) Surrounding her are pictograms meant to be read as symbols (images of concepts that are too large to be expressed but with the help of analogies taken from our physical world).

When we unite the rhombs (each consisting of four rhombs) to Medusa’s left and right and likewise the concentric circles with each other they create an invisual cross. This cross is furthermore strengthened by the swastika to the left of the figure that in its turn is reiterated on the birds’ wings and on the naked leg.

The three triangles, divided in three parts and with a spiral on top may allude not only to the Lady and her two sisters, but also to the unity of the goddesses who are both one and three, child, woman, and crone.

These same abstract pictograms are used on the rim of plates found in Knossos, Crete, and Al Mina in Syria. They are a generation younger, but clearly show the influence from this Rhodian plate.

In the late Bronze Age tombs, the deceased often wears a belt decorated with wild geese symbolizing a new birth. For once, there is a myth backing up the image: In the Trojan war Hera fights for the Greeks against Zeus’ explicit command that the Olympic goddesses and gods be neutral. Once when she really needs to distract Zeus she asks Aphrodite to lend her the belt of sexual passion. Zeus is inflamed and they make love. Flowers grow up around them while the sky covers them with a glittering cloud of gold. (The Iliad 14: 214, 345 ff).

In the late Bronze Age tombs, the deceased often wears a belt decorated with wild geese symbolizing a new birth. For once, there is a myth backing up the image: In the Trojan war Hera fights for the Greeks against Zeus’ explicit command that the Olympic goddesses and gods be neutral. Once when she really needs to distract Zeus she asks Aphrodite to lend her the belt of sexual passion. Zeus is inflamed and they make love. Flowers grow up around them while the sky covers them with a glittering cloud of gold. (The Iliad 14: 214, 345 ff).

Love-making generates new life and the wild goose is the symbol of the goddess that brings the power to conceive to the future mother. 3.600 fibulas (security pins) decorated with geese were found in tombs on Rhodos.

Nine (five plus three) pomegranates hang from the wings down on the Lady’s arms. They are common on Rhodian gold jewelry being important symbols of fertility – new life – and in a special way characterize Aphrodite, Athena, Demeter and Persephone.

The symbolic images surrounding the Lady and painted on her body already make it clear the the artist has meant to paint an image of the importance of the goddess. Medusa, the Lady, is too big to be enclosed: She is the cross and the center not only of the cross, but also of the circles; She is the unity of number three in the triangles. She is the Mistress of physical love empowering women to conceive new life.

In the next blog I’ll discuss the mask and the eyes, the wings and the water-birds that enlarge and concentrate the symbol that is the Lady even more.

***

Illustrations:

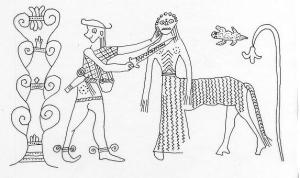

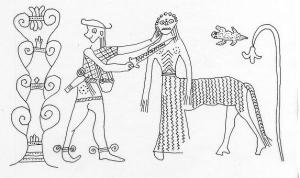

Perseus killing the Gorgo Medusa. Detail of an amphora from Tenos found in Thebes in Boeotia, c. 700 – 660 BC. In the Louvre CA 795. Drawing K.B.

The Great Goddess from Rhodos. Inside of a plate from a tomb in Kamiros, Rhodos, now in the British Museum Acc. 60.4-4-2. After Hirmer 561.0248 , Photo Archive, Getty Library, Malibu. Drawing K.B.

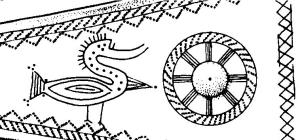

Rim- fragment of plate from Knossos, Crete. After H. Payne. “Early Greek Vases from Knossos,” BSA 29, 1929, Pl. 10, 7. Drawing K.B.

Similar fragment from Al Mina, Syria. After M. Robertson. “The excavations Al Mina, ” JHS 60, 1040 fig 5 g. Drawing K.B.

Details of belt with goose and elaborate circle. From tomb EE 12, Quattro Fontanile, Veio. Excavations of the British School in Rome. Drawing K. Berggren.

Medusa: The Questions

Who is Medusa? Ancient and modern writers, all prominent men and women, tell us that she was a monster, but was she really?

Luisa Banti once pointed out that the ancient Greeks had such a high opinion of human dignity that they imagined their gods exactly as themselves. They still influence us. We cannot imagine that an artist wants to represent a divinity as a mixture of an animal and a human being, forgetting that what we think of as evil (the snakes, for example) others may experience in a different manner. We regard Medusa through cultural lenses. Let me give you some examples.

Giuliana Riccioni discussing the scene on the vase from Tenos shown above writes that “Medusa’s human face wears an extremely rigid expression . . . eyes wide open with dilated pupils . . . The long thin arms hang lifeless long the body, the hands being nearly fleshless, the fingers extremely long show the thin bony claws . . .”

Another archaeologist, Thalia P. Howe cites Pindar’s twelfth Pythian Ode where he says that the sound of the flute “imitates the cry exceedingly shrill that bursts from the hungry jaws of Euryale.” She proposes that in order to convey the idea of a terrifying noise Medusa appears with a great distended mouth.

The French historian and anthropologist Jean-Pierre Vernant follows Howe saying that the Gorgon is more animal than human; her face is more a grimace than a face.

For the psychologist Erich Neumann she incarnates the negative elementary character: “the Gorgon is the counterpart of the life womb . . . she is the womb of death or the night sun”.

Edward Edinger, another well-known psychologist, writes that “the classical example of the benumbing, paralyzing aspect of the negative feminine principle is the myth of the Gorgon Medusa”.

Another psychologist, Edward Whitmont although recognizing that destruction gives birth to change and re-creation sees Medusa as the angry or insulted Feminine. Discussing new models of orientation he writes: “They all aim at transforming the chaotic power of the abysmal Yin, the Medusa, into the play of life. They mediate the terrifying face of the Gorgon into the helpful one of Athena”.  Even Marija Gimbutas uses the same lenses. Although she acknowledges that Medusa once was a potent goddess, she sees “a grinning mask with glaring eyes … lolling tongue, projecting teeth, and writhing snakes for hair” and understands her as the dangerous, dark side of Artemis.

Even Marija Gimbutas uses the same lenses. Although she acknowledges that Medusa once was a potent goddess, she sees “a grinning mask with glaring eyes … lolling tongue, projecting teeth, and writhing snakes for hair” and understands her as the dangerous, dark side of Artemis.

Judging from the paintings of Medusa’s severed head painted by Caravaggio and Rubens five hundred years ago, I wonder if it wasn’t then that Medusa became the image of all evil incarnated by and projected on the archetypal Woman. These images and the modern ones easily found in Google agree with Edinger and Whitmont. They are so filled with emotions that only with great difficulty can we liberate ourselves from regarding Medusa as the personification of evil – but it is possible.

The first step is to consider that her names – Medousa, Queen, Lady, Mistress; Sthenno, the Strong, Mighty One; Euryale, the Wanderer; and Gorgo, the lively Horse, the divine Centaur – point to her being a goddess.

The second step is to remember that prehistoric artists were not interested in portraits; they were frantically trying to make the invisible Holy visible. When we content ourselves with glancing at them we loose sight of how the artists tried to solve the impossible task they have set themselves.

The questions I intend to ask and perhaps find an answer to are why the Lady — the Mighty Wanderer, the Spirited Horse — consented to be killed by Perseus, an adolescent, not yet a grown man? Isn’t it the sin of hubris, insolent pride against the gods to imagine that a mere mortal can kill an immortal being?

What happens to a people, a state, a culture that permits such a killing? This is my second question.

In order to find answers we first must understand who Medusa is. Her names indicate that she is a goddess. As no goddess by this name exists in the Greek pantheon, which of the goddesses is she? Athena? Hera? Artemis? Demeter? Hekate? Persephone?

The answer is hidden in the archaic images in which Medusa is represented alone, without Perseus. There are very many of them, many more that those showing her dead body. I have chosen four of them:

A pottery plate from the Greek island of Rhodes,

two bronze plaques found in Olympia in the Western Peloponnese,

the West pediment of Artemis’ temple on the island of Corfu,

and the bronze statue that once crowned the oldest Parthenon on the Acropolis of Athens.

The detailed descriptions will be tedious, but as it is the only way for us to really see the details – and they are as important as the whole picture – I do ask for your understanding and patience.

***

Illustrations:

Perseus killing the Gorgo Medusa. Detail of an amphora from Tenos found in Thebes in Boeotia, c. 700 – 660 BC. In the Louvre CA 795. Drawing K.B.

Medusa by Caravaggio (1571 – 1610) in Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Medusa_by_Carvaggio.jpg

Medusa by Rubens (1577 – 1640). Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Rubens_Medusa.jpeg

Medusa: The Earliest Image

In the early seventh century BC, when Thebes, Corinth, Sparta and some of the Greek islands were culturally more advanced than Athens, there was a woman potter on the island of Tenos who began retelling myths in her art. She must have been a quite famous artist at the time, because some of her large vases were exported as far as Thebes in Boeotia and the island of Mykonos.

Two of her amphoras in Thebes survived the centuries buried in a tomb, and one of them is now preserved in the Louvre. The beautiful stylized image on the vase depicts the killing of Medusa by Perseus, and we easily recognize the myth because the picture of Perseus follows closely the description in the Shield of Herakles, supposedly written by the great poet Hesiod. The interesting fact is that, although the Shield of Herakles was written in the eighth century, the description of Perseus was added at least one hundred years later. Here we have an instance when the image influenced a poet.

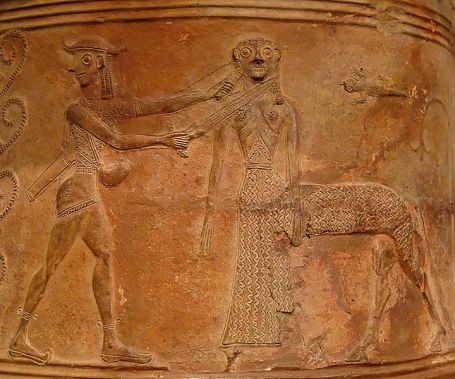

As in the description, Perseus is depicted as a beardless adolescent wearing a short tunic , the “invisibility” hat, a “sword with black sheath across his shoulders” and a “silver bag” hanging from his neck. He is rendered in profile turning his head away from Medusa, while gripping her hair with his left hand so hard that her lips are drawn back because of the strain, and holding the sword to her throat with his right hand.

Medusa’s human figure stands in the same position as the earliest cult statues, the xoana, made of wood. She is a goddess who has taken human shape and she is also a centaur.

Her horse legs are posed in the same warrior stance that Perseus keeps (in yoga called Virabhadrasana), implying readiness for battle. If it had been her wish she could easily have overpowered the boy. She is not directing her gaze at him. He is in no danger.

Centaurs

Medusa is the only Greek female centaur; the others are all men/stallions. The image came to Greece from the Near East where centaurs were close to the gods. The seal cylinder with a centaur from the Babylonian Nippur below is a good example. It is dated in the middle of the fourteenth century BC, that is, contemporaneously with the Mycenaean civilization in Greece.

The centaur has small wings; is dressed in a shirt with tassels on the sleeves and has a spotted skin knotted round the waist and draped over the horse’s back. A quiver hangs on his back and he is galloping so fast that the tail is blowing with the wind and at the same time he shoots an unfeathered arrow from his bow. Flowers are growing below him and a flowering tree stands in front of him. Strength, power and beauty flows from the image.

To understand a little of the emotions that inspired the archaic feelings about centaurs let us look at the horse. Aniela Jaffé points out that when animals appear in myths, sagas and dreams they seem to be our dormant instincts trying to return to consciousness and recreate a lost wholeness. This may be the reason why children project much of their emotions of fear, awe and love on the horse.

I remember my own exhilarating feelings when one summer I played at being horse and rider. I was contemporaneously the strong, swift horse and the rider using her intelligence, will and emphathy to make the horse obey. Growing up continuously stumbling and falling over my own feet, continuously being told to be quiet and stop making faces I didn’t know I was making, the freedom and strenght I felt being the horse and its rider was indescribable. Growing older I lost this feeling, but I recognize it in the description that Xenophon makes, in the fourth century BC:

Now the creature that I have envied most is, I think, the Centaur (if any such being ever existed), able to reason with a man’s intelligence and to manufacture with his hands what he needed, while he possessed the fleetness and strength of a horse so as to overtake whatever ran before him and to knock down whatever stood in his way. Well, all his advantages I combine in myself as a horseman.

Horses are among the few animals that allow us to enter in symbiosis with them. In fact, it is only when this symbiosis exists that the rider not only is carried by the horse, but truly rides it and the horse not only pulls the chariot, but the charioteer and horse work together, the horse sacrificing to the human part some of its own power and freedom. Perhaps this is the reason why, as Ludolf Malten points out, the accent in Greek literature always lies on the horse and not on the rider, not even on the god that takes its shape.

The horse seems to have been tamed in Greece during the early Mycenaean period, around 1900 BC. During more than one thousand years it is only represented as pulling the chariot although in order to control a herd of horses one must be on horseback.

Perhaps the chariots were so full of prestige and legend that the public concentrated on them and not on the simple rider. Light chariots had been introduced in the early second millennium BC first in Egypt and the Middle East, then in Crete by the Mycenaean Greeks. It was no problem for Pharaoh to drive a chariot in Egypt, but in Bronze Age Europe it was virtually impossible. Some Mycenaean roads have been found, but Homer’s description how Telemachus drives from Pylos to Sparta shows how traveling in a chariot had become a fantasy in Greece telling the story as if the high mountain Taygetos had not existed. Until less than thirty years ago, when the road from the West was united to the road coming East from Sparta it was impossible to cross the mountain with a vehicle. If Telemachus had indeed crossed it and not taken the long way round, he would have been forced to carry the chariot!

The fact that Medusa is centaur explains her name, Gorgo; that her two sisters are called Gorgons; that the head is a Gorgoneion.

After the archaic period Gorgo began to signify the horrible monster that killed by the look of her eyes, but used about a horse it continued to mean “hot, spirited.” We also must not forget that the most famous woman in Greek history was called Gorgo. She was the daughter of king Cleomenes of Sparta and later married the famous Spartan general Leonidas. Herodotos admiringly mentions her twize for her great intelligence. She certainly was not named after a monster, but after a spirited, beautiful horse.

I therefore propose that in archaic times Medusa in her animal shape of a wild horse was called gorgós – “hot, spirited, fierce” – because that is what a wild, beautiful horse is. The viewer thus sees the divinity of Medusa in the beautiful and fierce, wild horse and in the dual image of cult statue and horse. She is non-human femininity, a being totally different from us, but whom with the help of analogies we are able to emotionally bond with.

***

Illustrations:

Perseus killing the Gorgo Medusa. Detail of an amphora from Tenos found in Thebes in Boeotia, c. 700 – 660 BC. In the Louvre CA 795. Photo Jastrow for Wikimedia Common. http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Perseus_Medusa_Louvre_CA795.jpg

Centaur. Ca. 1350 BC from a cylinder seal from Nippur, Babylonia. After Paul Baur, Centaurs in ancient art. 1912, fig. 2. Drawing K.B.

Medusa: Homer and Hesiod

Surprisingly few ancient authors mention Medusa and Perseus although the story seems to have circulated from at least the beginning of seventh century BC. The most ancient poets, Homer and Hesiod, don’t tell the story in its wholeness but from their poems it is clear that they they knew something about it.

In the fourteenth song of the Iliad – orally composed by Homer, on the East coast of what nowadays is Turkey, sometime between the eleventh and ninth centuries BC and perhaps written down in the late sixth century Athens – Perseus is presented to the listeners as if he was already well known by them. In 4:319, Homer lets Zeus present him, “the most famous of all men” as his son with Danae. Perhaps G. Mylonas is right and a tale about Perseus, king of Mycenae around 1350 BC, was sung already in the Mycenaean palaces.

Medusa, the dreadful monster, is mentioned three times. However, both Adolf Furtwängler and Ulrich von Milamowitz-Moellendorff considered them as later additions and as far as I know nobody has tried to falsify their proposal.

The line in the fifth song is the most evident one. Here we read that Athena puts the aegis (a buff-coat or protective corset) over her head and on this corset she wears the “horrible monster’s, Gorgo’s head”, but the vase-paintings show that this happened only in the last quarter of the sixth century BC, that is, several hundred years after Homer. Thus, the Iliad only tells us that a story about Perseus, son of Zeus and Danae, was known early on.

The second early Greek poet was Hesiod from Boeotia, who perhaps lived in the eighth century BC. He composed a poem, the Theogony, about the creation of the world and the Greek gods, only one generation before an artist from the island of Tenos made the earliest image of Perseus killing Medusa. Unfortunately for us, Hesiod is more interested in Pegasos than in that story, but he does tell us that the monsters were three and not one: the mortal Médousa, whose name comes from the old verb médô that means “I rule,” and her two immortal sisters, Sthenno that means “the strong one” and Euryále “the one that wanders widely.” He also tells us that Poseidon, the “Dark-haired One,” whom Zeus had made the ruler over the Mediterranean Sea, made love to Medusa “in a soft, grassy meadow among the flowers,” and that “when Perseus cut off her head, Chrysaor the Great and Pegasos the Horse leaped out” (verses 274-86).

However, we don’t find any description of the “monster” with lolling tongue and big teeth until in the fifth century in Pherekydes and Euripedes and the snakes are not mentioned at all until Ovid writes about them. Luckily we have the images and they tell us a more complicated story.

Child of Water

Child of Water (or Grandchild of Water) is Apam Napat, the Hindu god of fire that is born from fresh water. I also tell the stories how Inanna was killed by her sister and returned to life when the Water of Life was sprinkled on her, and how the terrifying monster Medusa, in modern Greece, has become a strict and kind goddess of the sea.